METROPOLIS

ZM

I have these strange dreams. I walk London’s streets and I am a giant. I tower over the skyline, the Gherkin the Walky-talky the Cheese-grater the Shard. I glance down at them as I follow the river. Sometimes I walk all the way out to the edge, to the Thames Barrier Greenwich Barking Wanstead. I walk to the marshes, I put my hands in the mud. I find the overlap, where the layer of the city ends. I peel it up, I pull at it. The city scrunches in my hands like plastic packaging. I peel some more. I scrunch and crumple and collapse it all down. Sometimes I fold it up like a beach towel. The dreams always go the same way. I am very very large and the city is small and tight around me. It is a layer that has nestled down over something else. It is malleable, peelable, I can collapse it down, put it in its carry case, take it with me wherever I go. I dream of a city that doesn’t swallow me.

Well, this is what they say: London is a city of villages. The City of London proper was Old Roman Londinium (before that, it was rolling countryside). The city was contained in its walls, outside was villages and cemeteries. Then it was Lundenwic, then Lundenburh, then Lunden (London). But the city spilled out over its walls, swallowing the villages and cemeteries. Hampstead, Hornsey, Islington, Chelsea, Whitechapel — all villages! The city ate them, absorbed them, continued its sprawl over village and field. The city is an expansionist project. The city is a layer that gets plastered over whatever. In my dreams my nails find the edges, my nails dig the layer loose, and I peel the city off the land.

Because, this is what I say: the city is a fantastic projection. We all think it exists but are any of us really sure? It could really all just be a shared delusion. And are we really sure my delusion is the same as your delusion? Maybe the city is the build up of all our personal fantasies, overlapping into a crust. My city is Lordship Rec and the suburbs and the North Circ and the right half of the piccadilly line and the left half of the Victoria Line and my new flat (where I haven’t beaten the bounds yet so it is only a shimmering cloud around the canal). This is my contribution to the crust.

Guy Debord (if he were here) might say that the city is a set of limits, which can be negotiated or transgressed. He would say that the city is constructed in a particular way, it has prescribed routes —and what are we all doing, bowing into submission like this? A limit is only a posed question. You can bump the barriers, jack a lime bike and wheel off down the street clicking. The whole city will be open before you. Gary Budden would say that he wrote a whole book called London Incognita, full of arcane mythology about the city’s various zones that only seem to exist for its inhabitants (not the visitor) — that is a city that produces a subliminal folk culture underneath the limits imposed by the powers above. 10FOOT would say, yes, there is a city under the city (and over the city) that exists for those willing to explore all its hidden tunnels and corners. Sadiq Khan would say that the city is a fantastic melting pot of places and faces, and he’s pedestrianised Oxford Street, wonderful moneymaker. The Isle of Dogs should all be an oxbow lake, but the bankers poured concrete into the riverbank — so if you ask them, the city defies nature itself, all for the noble purpose of peddling global debt or betting on the end of the world or whatever it is they do all day.

Our crust, our fantastic projections — none of these things are real! They are only held together in our minds. We make the city, and it makes us — Guy Debord would continue what he was saying about psychogeography, derive, the flaneur, the way the city affects us as we all move through it and the way this movement can be approached with the spirit of experimentation. Maybe Guy Debord would take us on a walking tour. Down Whitechapel Road, somewhere between Aldgate East and Whitechapel station, we would turn down Greatorex Street. Between a taxi company and a leather shop, we would come upon a metal gate. This spirit of experimentation would lead us through a yard, into a warehouse and its dark corridor, all the way down to a door at the end. There, Guy Debord would lead us through a gallery space — he would wave his hand and say, this is not what we are here to look at — round the corner, into a room round the side. Guy Debord would announce: this is Jacob Sirkin’s studio, he has cleared it out to host a group show called Metropolis.

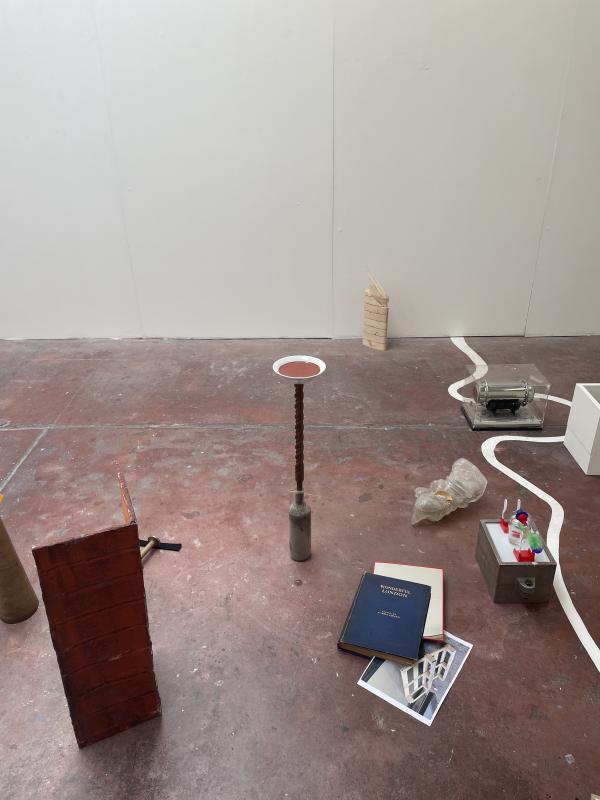

Me and Guy would look over the room. The floor of the studio would be cut in half by a massive white line winding across (the Thames). We would consult the press release: the 18 artists in this show have responded to a place in the city, the floor is actually a map, all the works are dotted across the floor and arranged according to the place’s location on London’s map. Me and Guy Debord, we would step carefully through the miniature city, like giants, glancing down as we follow the river.

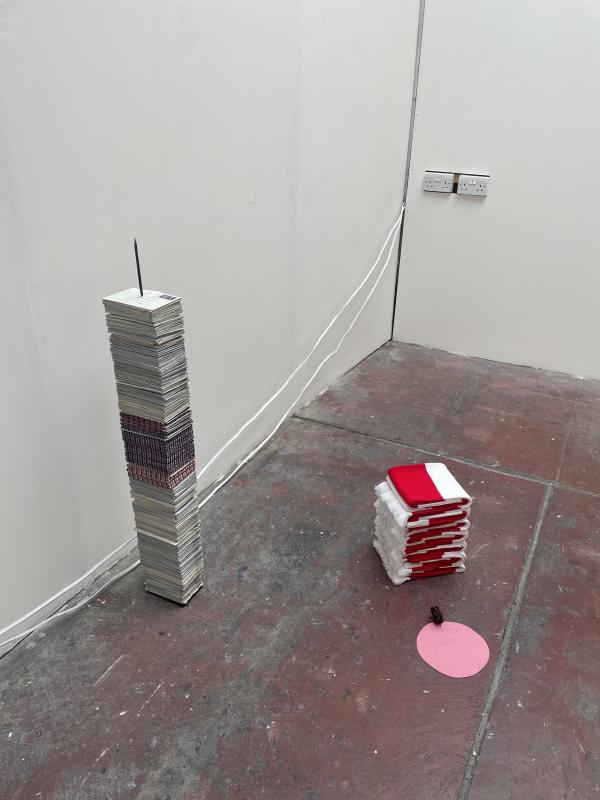

The works would be an assemblage. Paul Deller’s Love Letters to N13, a neat stack of letters speared through with a waist-high steel spike, cropping up far north like a high-rise tower. Luca George’s Big Ben, a cardboard remake of the clock tower, the bottom of a plastic bottle as the clock face. Some of the works would be sharp symbolic comedy: Henry Galano’s 14 sits on the location of Tottenham Hotspur Stadium, it is a stack of Arsenal scarves. Some would be esoteric in the way London is esoteric: Katherine Harrison’s Again and Again on the site of the London Mithraeum — the ruins of an ancient Roman temple for a mystery cult that was excavated from under the Bloomberg building. This work is a dippy bird toy that bobs its head back and forward into a glass of water (the functioning bird is facing the bodiless legs of a twin bird, one dips, one stands). Some would be coded mysteries that I have to figure out by googling: Tarzan Kingofthejungle’s Epilogue on 138 Piccadilly, a stack of registered office mail on a pile of soil that is actually Transylvanian earth — when I google the address, the search results tell me this is believed to be the London address of Count Dracula in Bram Stoker’s novel. And some would remain mysteries: Paul-Auguste Richard Ceccherelli’s Disjunction Trunk 6 & 7 wood logs and plastic rolls on two SW postcodes that turn out to be Victoria and Sloane Square stations — I don’t know why. Some of the works would be about labour and the container of this show itself: Corey Bartle-Sanderson’s Gnom mit karotte (glout), a hollow resin cast of a garden gnome full of the curator’s loose change and gallery floor mop water. Some would be about development and the container of the city itself: William Lucas’s Mason Richards Partnership for Castlemore Securities, a perfect building carved from wood — Castlemore Securities was a huge property development firm that collapsed after the 2008 financial crisis, Mason Richards Partnership are an architectural firm that designed several of their projects. Some would speak of the city’s people: James Sibley’s Home, a collection of containers full of liquids (apple cider vinegar, dish soap) and cling filmed shut. Or of its communities: London Art Service’s mini-gallery diorama of a show within this show, featuring works by Gianna T, Billy Fraser, Bobby Heffernan, Carmen Gray, Florence Sweeney and Vincent Matuschka.

Me and Guy Debord would survey this miniature city of objects and assemblage. The works would reward us for our looking. They would be curious, coded, many of them would be loving. A conversation about site or place would feel trite, a conversation about the found object would feel like a proxy — like you’re really trying to speak about something far more unspeakable. The city is a fiction built by the people within it (and without it), a crust of their delusions. The city is a layer, there is an above, there is a below. My favourite work in this show: Massimiliano Gottardi’s Untitled, a wine bottle full of concrete with a huge drill bit protruding from the neck, a bowl with red silt balanced precariously on top. It is 121 Mortimer Road, the former home of the Mole Man of Hackney — a man who dug an extensive network of tunnels underneath his terraced house in De Beauvoir, because he wanted ‘a really big basement’. His tunnels reached all the way to Dalston, he dug so deep he tunnelled into railway lines and the water table. Eventually a sinkhole caved in the road outside his house and Hackney Council evicted him. It is my favourite because I love that the Mole Man of Hackney existed. I like that the bottle feels so close to breaking, I love that the concrete is so solid, I love that the bowl is so precarious, I love that I want to kick it over and I love that I am able to resist. Art that speaks of this city often fails because it can only speak partially. Somewhere in all this partial talk, Metropolis would piece together something whole.

I have these strange dreams. I slide through the sewers and I am the Whitechapel fatberg. I am rippled grease and wet wipes and hair clumps and dried soap scum. I am full of mould, full of life. I am of this city, I am all of you. I am the lipids from your conditioner, the grease on your fork, your floss and cooking fat. I would dream of the city above me, its warmth. The city feels large, a skin that contains me. A city is only a collection of trinkets interlocking in a chain link, unexpected assemblage. I would wait for these objects to fall below, to fall to me. I am swallowed by this city, but I am swallowing it too, I am it’s crust made flesh! Beneath the city, in its pipes and caves, I am sliding towards the tide in the wet and dark.